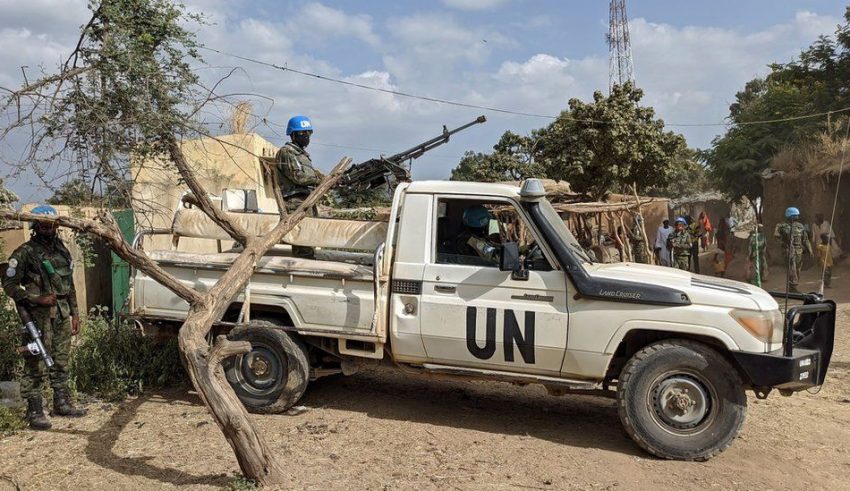

As international peacekeepers prepare to finally leave Sudan’s war-torn Darfur region, concerns are growing for the safety of civilians if the new fragile peace deal there fails, as the BBC’s Mike Thomson reports.

Fourteen-year-old Abdullah sits on an old tyre outside a ramshackle hut in a sprawling, impoverished camp for displaced people.

He was born in Abu Shouk camp, just outside Fasher in North Darfur, where he has spent his entire life – he has never seen the village his family calls home.

“I’ve been told that my family and other relatives were living together in a very beautiful village surrounded by green land.

“My parents have told me that it was a lovely place and that life was so much better there.”

Abdullah, who has only seen a television once in his life, lives in fear of armed gangs who often raid the camp at night.

“We have to hide, there’s nothing more we can do. If you confront them you’ll be attacked.”

It is hoped that a recent peace deal will enable Abdullah and his family to go home, and finally put an end to the 17-year-long conflict in Darfur, which has left 300,000 people dead and forced 2.5 million people to flee their homes.

The violence began back in 2003 when armed groups there rebelled against the government, claiming their region was neglected.

Khartoum responded by arming Arab nomad herders, who became known as the notorious Janjaweed, and paying them to brutally supress the uprising.

Most rebel groups have now signed a peace agreement with the government, but at least 1.5 million people, like Abdullah, remain in around 60 camps spread across Darfur.

Most, like Zara, who has been in Abu Shouk camp for 17 years, ache to go home, but still can’t.

“We cannot go to farm our lands simply because they’re occupied by others. They’re the ones who killed us, they’re the ones who displaced us, and we’re still here.”

‘Every day is killing’

A trip to the jittery town of Nertiti, about six hours drive from Abu Shouk camp, highlights another reason why many displaced people are still refusing to go home.

Most farmers there are too afraid to go into their fields following numerous killings and rapes.

Those in the town itself clearly are not safe either.

Armed groups, described as Janjaweed, recently shot dead Khadiga Ishag’s husband and one of her sons before shooting her too at their home in Nertiti.

“Every day is crisis, every day is killing,” she said.

“We don’t trust our government, the military or the police, we really don’t trust them at all. If a solution isn’t found there will be genocide here.”

The reason Khadiga and others are frightened of the army is that its ranks have long contained many former Janjaweed fighters, the very people who terrorised them for so long.

Not only that but under the new peace deal members of other armed groups are to be amalgamated into the Sudanese military.

There is another reason too.

At the end of December the international peacekeeping force Unamid, once the biggest in he world, is finally pulling out of Sudan after 13 years.

Despite the widely held belief that this combined United Nations-African Union force has not always been effective in protecting civilians here, its presence is thought to have helped curb abuses by the security forces.

False dawns

Many are pinning their hopes on the country’s new half-civilian-half-military transitional government.

It came to power after mass street protests in 2019 toppled former President Omar al-Bashir after 30 years of dictatorial rule.

He has since been jailed on corruption charges and stands accused by the International Criminal Court of war crimes in Darfur.

Sudan’s Minister of Culture and Information, Faisal Mohammed Mohammed Salih, a former civil rights activist who was once jailed by the old regime, is part of the new look transitional government.

While accepting that there is widespread fear and distrust by civilians of the military, he insists that injustices will no longer be tolerated.

“All individuals accused of any kind of crime in Darfur will be put on trial. No-one will be exempt from this,” he said.

Under the peace agreement a land commission is also being set up to help people whose land has been taken while they have been in camps, as well as also looking into the rights of nomadic herders.

Yet back at Abu Shouk camp near Fasher, such measures mean little to those who have seen many false dawns since the conflict began in 2003.

It is perhaps toughest for the young, such as 14-year-old Abdullah, who have known nothing but conflict, hunger and displacement camps.

Sitting quietly outside his family’s hut he draws shapes in the sand with a twig, though his mind is clearly elsewhere.

“In my dreams I will have a life without threats, where people go safely to and from their farms.

“A place where I can have a decent life. But I do find it difficult to imagine this, because it would be so different to all I’ve known.”

Source: bbc.com