China is proposing to introduce a new security law in Hong Kong that could ban sedition, secession and subversion.

The move is likely to provoke strong opposition internationally and in Hong Kong, which was last year rocked by months of pro-democracy protests.

China’s delayed National People’s Congress, its legislature, will debate the issue when it opens on Friday.

Chinese media said the move defended national security, but opponents said it could be the “end of Hong Kong”.

Demonstrators in Hong Kong have repeatedly protested against what they see as a gradual erosion of the territory’s autonomy by the communist lead government in Beijing.

The BBC’s Robin Brant, in Shanghai, says that what makes the latest proposal so incendiary is that the Beijing government could bypass Hong Kong’s elected officials and simply impose the changes.

The last British governor of Hong Kong, Chris Patten, called the move a “comprehensive assault on the city’s autonomy”.

President Donald Trump said the US would react strongly if China followed through with its proposals.

- What is the Basic Law and how does it work?

- Why are there protests in Hong Kong? All the context you need

The Hong Kong dollar dropped sharply on Thursday in anticipation of the announcement.

What will the NPC do?

The issue has been introduced on the NPC agenda, under the title of Establishing and Improving the Legal System and Enforcement Mechanism of Hong Kong.

Hong Kong’s mini-constitution, the Basic Law, which provides the territory certain freedoms not available on the mainland, does require its government to bring in a security law. It had tried to enact the so-called “sedition law” in 2003 but more than 500,000 people took to the streets and it was dropped.

A spokesman for the NPC said on Thursday that China was planning to improve on the “one country, two systems” policy that Hong Kong has observed.

Zhang Yesui said: “National security is the bedrock underpinning the stability of the country. Safeguarding national security serves the fundamental interest of all Chinese, our Hong Kong compatriots included.”

Hong Kong is heading for elections to its own legislature in September and if last year’s success for pro-democracy parties in district elections is repeated, government bills could be blocked.

A mainland source told the South China Morning Post that Beijing had decided Hong Kong would not be able to pass its own security law and the NPC would have to act.

- Profile: Carrie Lam, Chief Executive of Hong Kong

China has the option to impose it into Annex III of the Basic Law, which covers national laws that must be observed in Hong Kong.

The opening of the NPC had been delayed because of the coronavirus outbreak.

What could be in the new law?

The NPC spokesman would only say that more details would come on Friday.

Sources say the law will target terrorist activity in Hong Kong and prohibit acts of sedition, subversion and secession, as well as foreign interference in Hong Kong’s affairs.

Pro-democracy activists fear it will be used to muzzle protests in defiance of the freedoms enshrined in the Basic Law.

Similar laws in China are used to silence opposition to the Communist Party.

What’s the initial reaction and will there be protests?

There have already been calls inside Hong Kong for demonstrations.

Democratic lawmaker Dennis Kwok told Reuters: “If this move takes place, ‘one country, two systems’ will be officially erased. This is the end of Hong Kong.”

He was echoed by Civic Party legislator, Tanya Chan, who said: “One country, one system has truly come to Hong Kong.” She said this was the “saddest day in Hong Kong history”.

Student activist and politician Joshua Wong tweeted that the move was an attempt by Beijing to “silence Hong Kongers’ critical voices with force and fear”.

![]()

The pro-Beijing DAB party said it “fully supported” the proposals, which were made “in response to Hong Kong’s rapidly worsening political situation in recent years”.

Pro-Beijing lawmaker Christopher Cheung added: “Legislation is necessary and the sooner the better.”

An editorial in the state-run China Daily said the law meant that “those who challenge national security will necessarily be held accountable for their behaviour”.

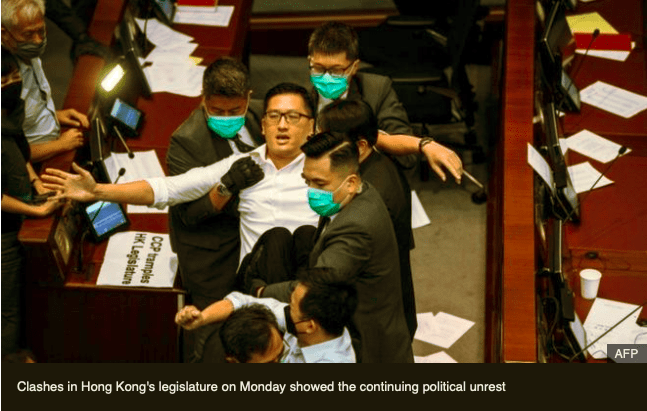

Political unrest had cooled during the coronavirus outbreak but its resurgence was apparent on Monday, when a number of pro-democracy lawmakers were dragged out of the legislative chamber during a row about a Chinese national anthem bill that would criminalise disrespect of it.

A group of 15 prominent pro-democracy activists also appeared in court on Monday charged with organising and taking part in unlawful assemblies related to last year’s protests. Five also face the more serious charge of incitement.

Millions took to the streets for seven months last year in rallies that began peacefully but later spiralled into violent clashes.

Those protests were initially about another controversial bill allowing extraditions to the mainland. It was later dropped.

China’s move also comes as the US is considering whether to extend Hong Kong’s preferential trading and investment privileges. It must decide by the end of the month. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo on Wednesday expressed concern over Hong Kong’s autonomy.

What is Hong Kong’s legal situation?

Hong Kong was ruled by Britain as a colony for more than 150 years up to 1997.

The Basic Law, which runs out in 2047, gives Hong Kong “a high degree of autonomy, except in foreign and defence affairs”.

As a result, Hong Kong’s own legal system, borders, and rights – including freedom of assembly and free speech – are protected.

For example, it is one of the few places in Chinese territory where people can commemorate the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown.

But Beijing has the ability to veto any changes to the political system and has, for example, ruled out direct election of the chief executive.

Source: BBC